JavaScipt Execution and the Event Loop

A brief introduction to JavaScript execution engine and the event loop

When you start off developing web applications, you think: What stack to use? What should the UX/UI look and feel? and so on, but you don’t think about how your code is being executed on the browser. This may affect the performance of your application and the browser itself, even some code running in a weird order.

This article talks about the JavaScript Execution and all the important process which goes into it. It will help people like myself, who are just starting off their programming careers, and for developers who want a refresher on the JavaScript Execution.

JavaScript Engine

Firstly, we need to understand how JavaScript as a language works and its constraints;

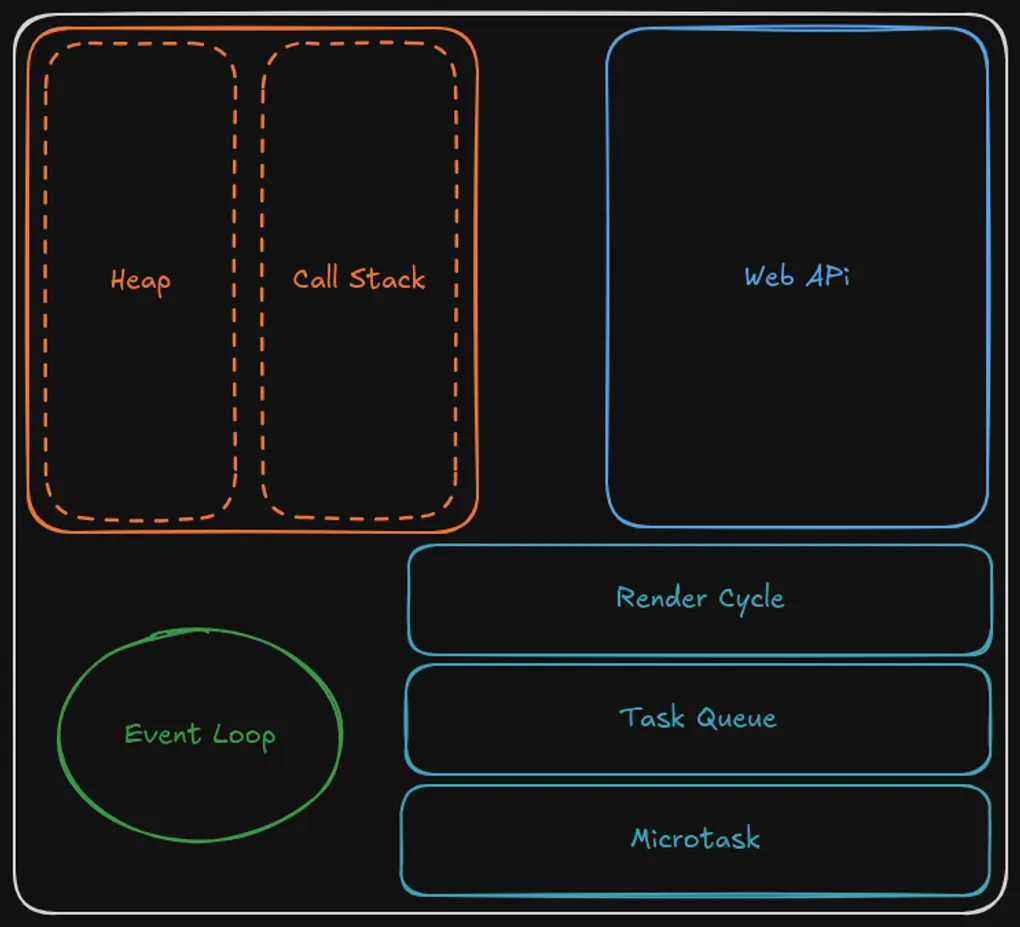

JavaScript is a single-threaded language, where one single process can be executed at a time. Process (or better known as a context) is created for the main body, functions and IIFE (Immediately Invoked Function Expression), during the creation phase, variables and function declarations are hoisted to the top of their scope. In addition to this, it tracks the next line in the program that should run and other crucial information to the contexts. After the creation phase, the execution context is placed in the call stack (last-in-first-out), and code runs line-by-line in the execution phase. Each execution context also has a scope chain that lets inner functions access outer variables, this is how closures work.

Alongside the call stack, there is a heap, simply put, a memory pool that helps with allocating memory to objects, we won’t talk about it more as it isn’t needed for this context but if you like to read more about it, you can do so at the MDN memory management article.

Let’s say we have a simple program which prints “Hello World” from a function.

View Call Stack Example

function greet() {

console.log("Hello World");

}

greet();

// Call Stack Flow:

// ┌─────────────────┐

// │ [global] │ ← Start here

// ├─────────────────┤

// │ greet() │ ← Pushed when called

// ├─────────────────┤

// │ console.log() │ ← Pushed inside greet

// ├─────────────────┤

// │ [empty] │ ← Popped back to global

// └─────────────────┘

As we can see, when the function is called a context is created for it in the call stack and then executes console.log("Hello World"); after all that we remove the context from the stack.

With all that being said, we run into an issue of not being able to run other processes alongside the main-thread, but that’s where the Event Loop comes in…

Event Loop

We can make the JavaScript become concurrent, which means we can execute multiple operations independently without necessarily running them simultaneously, by asynchronously delegating certain work to the browser.

If we decide to run a Web API such as setTimeout(cb, ms), setInterval(cb, ms), UI events or I/O anything inside will be delegated to the browser and when it’s resolved, the callback function is queued into the Task Queue (Macrotasks) which only executes when there is nothing on the Call-Stack.

View Event Loop Example

console.log("First");

setTimeout(() => {

console.log("Third - from Task Queue");

}, 1000);

console.log("Second");

// Execution:

// 1. "First" logs immediately

// 2. setTimeout() is handed to browser, 1s timer starts

// 3. "Second" logs immediately

// 4. After 1s, callback queues to Task Queue

// 5. When stack is empty, it executes: "Third"

So we can see the setTimeout() result is placed in the task queue and then run after all the other contexts are executed in the stack. One more note: setTimeout() doesn’t guarantee exact timing-it’s just a minimum delay.

setTimeout(cb, 0)Even with a delay of0ms, the callback still waits for the current stack to clear and microtasks to run.

View Microtask vs Macrotask Demo

console.log("1️⃣ Sync code");

setTimeout(() => {

console.log("5️⃣ Macrotask (Task Queue)");

}, 0);

Promise.resolve().then(() => {

console.log("3️⃣ First microtask");

Promise.resolve().then(() => {

console.log("4️⃣ Nested microtask");

});

});

console.log("2️⃣ More sync code");

// Output:

// 1️⃣ Sync code

// 2️⃣ More sync code

// 3️⃣ First microtask

// 4️⃣ Nested microtask

// 5️⃣ Macrotask (Task Queue)

// The Event Loop waits for:

// 1. Call stack to empty

// 2. ALL microtasks to finish (even nested ones)

// 3. Then takes 1 macrotask

Next, we come to Microtasks. Those are tasks which come from Promise resolves/rejects -> .then(), .catch(), .finally(), keep in mind the executor function runs immediately and synchronously and only after .then() is async, are added to the microtasks queue. async/await is similar as Promises, so await also queues microtasks. Again, we need to wait for all the tasks to be executed in the stack, and only then may microtasks start executing. All microtasks must be executed, even those additional microtasks which came from the microtasks themselves before moving to the task queue and the render cycle, as the microtasks run before the task queue.

View Microtask Queue Depth Example

console.log("Start");

Promise.resolve().then(() => {

console.log("Microtask 1");

// This queues *during* microtask execution

Promise.resolve().then(() => {

console.log("Microtask 2 (nested)");

});

});

setTimeout(() => {

console.log("Macrotask - this runs LAST");

}, 0);

console.log("End");

// All microtasks drain completely before any macrotask runs

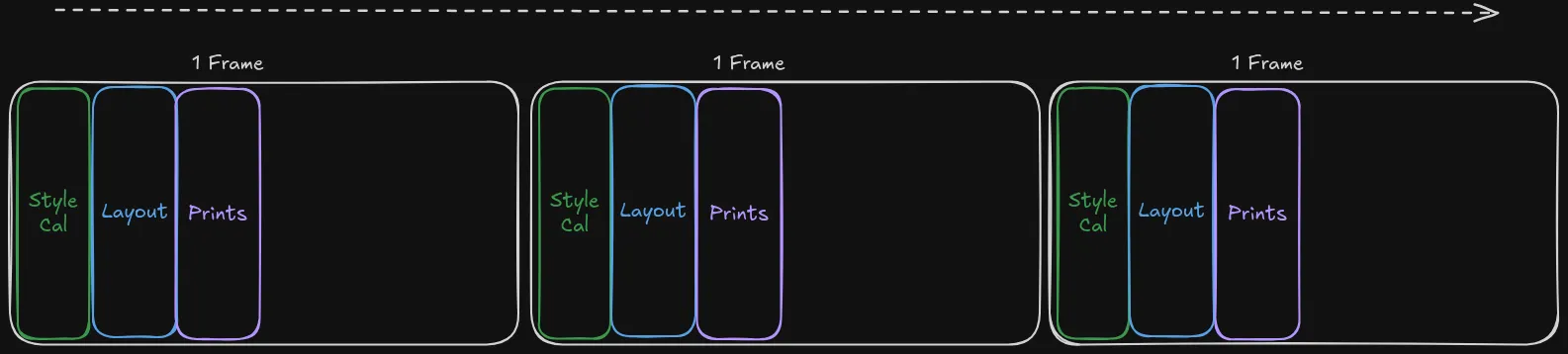

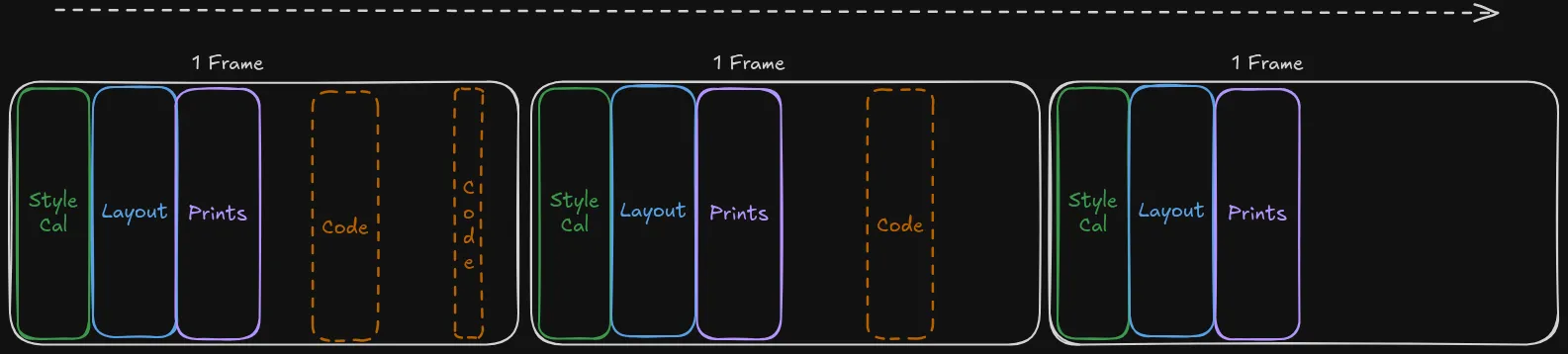

How Rendering fits in: Rendering happens after microtasks but before the next task queue, not “between” random queue items, there is a render cycle where the browser re-renders the Style Calculation -> Layout -> Painting aiming for ~16.67ms per frame (60 FPS), but only if the microtask queue is empty.

The browser aims to render at

~60fps, but only after the microtask queue is empty and before the next task queue.The code and the browser’s user interfaces run on the same thread:

When our function/process causes an infinite loop and for loops that blocks UI for

500ms, which makes the browser stall (Blocks everything: UI, Rendering, timers).Even when the browser might feel sluggish, it may be due to complex work by our code.

When setTimeout() changes the page, we wait for the task queue. The first frame may render before the callback runs, so changes appear in the next frame. So in the next frame the re-render will have the right changes.

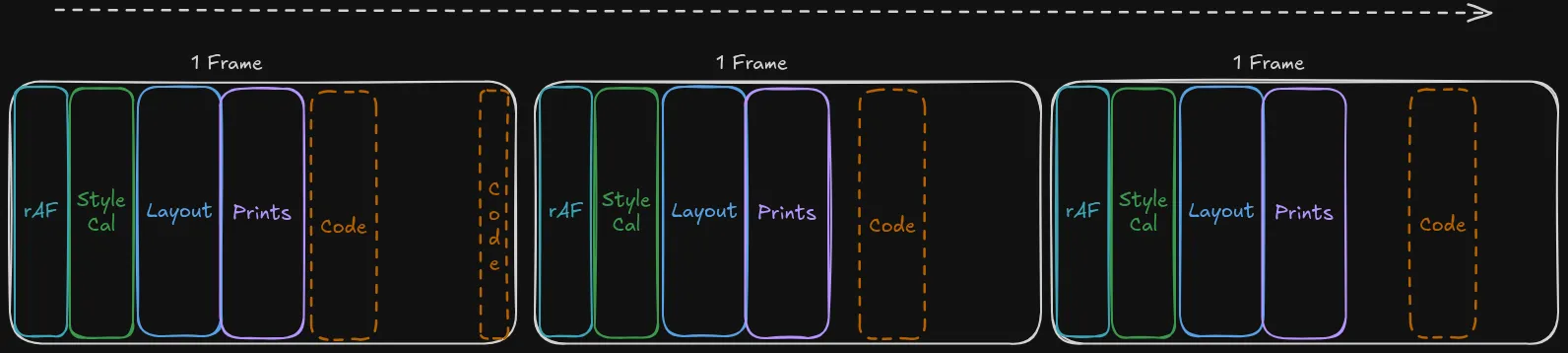

We can make those changes run as part of the re-render cycle by using functions like requestAnimationFrame(). After doing this, the order will become rAF -> Style Calculation -> Layout -> Paint. Enable the re-render to have the up to date data. The other processes are run as normal.

┌─ Call Stack empty? → YES → Drain ALL Microtasks

│ ↓

│ Render (if needed)

│ ↓

│ Execute 1 Task from Task Queue

│ ↓

└─ NO ←──────────── Keep executing current stackSummary

Key Takeaway: Microtasks always run before the next render or task queue. Use them for state changes, task queue for deferred work, and rAF for visual updates.

And that concludes our dive into the JavaScript Engine and the Event Loop. I hope it helped you get a deeper understanding. I’ll create similar articles about related topics.

References

Due to the length of the gifs, I’ve decided to link websites to visualize the flow:

-

MDN Documentation

JavaScript execution model

In depth: Microtasks and the JavaScript runtime environment -

Video Explanations

What the heck is the event loop anyway? | Philip Roberts | JSConf EU

Jake Archibald: The event loop, setTimeout, microtasks, rAF -

Interactive Visualizations

JavaScript Execution Flow (jsflow.info)

Alternative: Loupe by Philip Roberts